Causes

About The Group

About Stammering

Stuttering Explained

Typically the moment will be when there is an audience, and the message being communicated is important to the speaker or the listener. It is not straightforward to understand how or why this occurs. For example, in many who stutter a startling feature is that during a stuttered moment they are able to make a fluent aside (e.g. “gosh, this is difficult!”) and then go right back to stuttering on the phrase which was previously being stuttered. This suggests that stuttering is best understood with reference to language and communication, rather than being explicable purely within the framework of speech-motor control.

A strategy that might intuitively seem as if it would aid a transition from a blocked speech sound to the immediately following part of an intended message is for those who stutter to increase the effort to move on to the next speech sound. The basis for the supposition would be that we ordinarily have voluntary control of our speech musculature, and therefore a deliberate effort to make the next speech sound should be successful. However, when people who stutter redouble their efforts in this way, the clonic or tonic muscular activity will typically remain present in the background. As a result, the the redoubled effort is added on top of an already excessive amount of muscular tension. The result is frequently a burgeoning of clonic tension leading to chaotic oscillatory activity that manifests as jaw jerks, eye blinks and movements of head, limbs and other extremities; or else an increase in prolonged tension might manifest as exaggerated fixed postures. These externalisations are referred to as secondary stuttering, since they necessarily follow on from primary stuttering. The loss of control over speech musculature can be highly distressing for the speaker. It can also be perplexing to any listener who is without first hand experience of this type of stuttering, and who might reasonably wonder why the speaker is experiencing such difficulty executing a series of speech movements that seem as though they should be well within the speaker’s capability.

As well as being externalised, secondary stuttering can be internalised. Anxiety is an important factor through which to understand such internalisations. Commonly, stuttering co-occurs with anxiety. However, anxiety need not be causal, because anxiety is also a predictable and understandable consequence of repeated experiences of stuttering. This can often lead to confusion over cause and effect, since anxiety seems likely to have become internalised as a consequence of experiencing externalised stuttering, rather than (as has sometimes been proposed) externalised stuttering following from internalised anxiety.

Whatever its cause, anxiety around stuttering can develop into negative thoughts and feelings such as guilt and shame. As a result, repeated experiences of stuttering can lead to deliberate avoidance of speaking situations, or to substitution of words and phrases on which stuttering is not anticipated. This type of internalised secondary stuttering is sometimes referred to as “covert stuttering”, since the stuttered moments will frequently be invisible to the listener. Whilst limited use of covert strategies can be effective for some who stutter, for others a reliance on covert strategies will have profound psychosocial consequences and negatively impact quality of life. Maintenance of covert stuttering can become exhausting, and everyday social interactions that seem straightforward to many may be experienced as difficult or impossible for those who stutter. However, overt stuttering can have an impact comparable to covert stuttering, and thus replacement of covert stuttering with overt stuttering does not offer a panacea. Thus, the person who stutters can become captured between undesirable alternatives – e.g. to speak or not to speak; to stutter overtly or to use covert strategies; to make a video call or to use email; and so on. Following such reasoning, stuttering has been referred to as an “approach-avoidance conflict”, placing it in a class of psychological situations long understood to be among the most challenging to resolve.

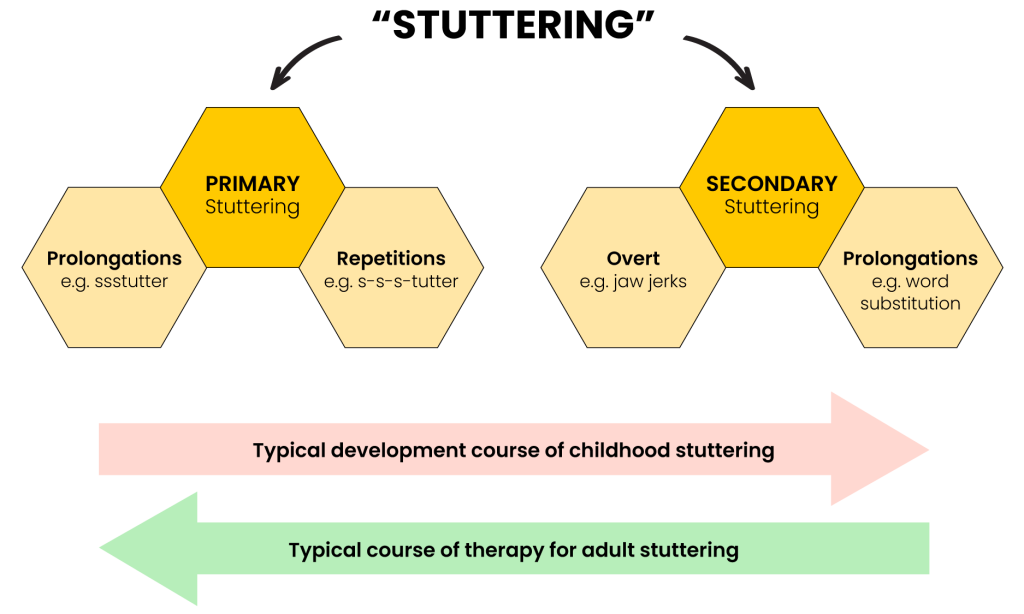

Often, people use “stuttering” as an umbrella term. However, as already described, there are several different types of stuttering. Discussion of stuttering can often be improved by specifying exactly what type of stuttering is being referred to. The diagram below shows how primary, secondary, overt and covert stuttering relate to each other.

The diagram also shows typical developmental and therapy routes for stuttering. Most stuttering has an onset in childhood, when aged around 3–4 years. At first, childhood stuttering will typically display the characteristics of primary stuttering. However, children can soon become aware of their stuttering. Frequently they will try to resolve the stuttering by increasing effort while speaking, but as already described this intuitive strategy is rarely successful, leading instead to secondary stuttering. For this reason, a cardinal principle of childhood therapies is to prevent secondary stuttering from becoming engrained. Whereas in adults who stutter, for whom secondary stuttering has frequently become deep-rooted, an aim is to unlearn secondary stuttering and return to something like the simple prolongations and repetitions of primary stuttering. Between 5–8 per cent of children will experience stuttering to some degree, although this is usually transient with the stuttering stopping apparently of its own accord a few months or years after it starts. Because many children stop stuttering at about the same time other children start stuttering, only about 1–2% of children stutter at any point in time. About 70% of this childhood onset stuttering has a genetic basis. It is not well understood what the other causes of childhood stuttering are, why some children stop stuttering whilst others continue to stutter, or whether it is possible to increase the likelihood of children stopping stuttering (or continuing to stutter) through interventions. Among the general adult population about 0.5% of people stutter overtly, and no more than about 0.3 % of adults have stuttering which is entirely covert.

Data consistently show that childhood onset stuttering diminishes across the lifespan. This may not occur for every individual, however in general people who began to stutter as children will either stop stuttering, or will stutter less, as they get older. This makes stuttering fundamentally different from neurodivergent diagnoses such as ADHD or autism, which do not change with age. Interestingly, the indication is that rates at which non-stuttering diagnoses co-occur with stuttering may be 50 % or greater. Speech or language diagnoses other than stuttering are among the most frequently identified, followed by anxiety and ADHD/ADD.

The experience of stuttering can be highly distressing. In an attempt to rationalise communicative breakdown, speakers might blame themself. They might also blame the listener. Such reactions are rarely helpful, although accepting the stuttering as is can be difficult for all parties to a conversation. There is accordingly a wide range of thoughts and attitudes around stuttering. It may take many years for people who stutter to establish their own speaking identity. While doing so it may help to talk to others who stutter, or to professional speech and language therapists. In person support groups run by people who stammer, such as Manchester Stammering Community or the many others groups available around the country, can offer useful resources for those who are embarking on a journey connected to stuttering.

If you’ve read this far, and are still wondering whether a stammering support group is right for you, then you should probably attend one. However, there is no urgency – take your time, and don’t do anything before you’re ready. You may like to try out several different types of support group, including online groups, to get a feel for what is likely to work for you. Our resources page contains a variety of starting points, and we hope you can find what you are looking for. Good luck with your journey!

Find Your Voice with Us!

If you stammer, you are not alone!

Join Our Stammering Community for Support and Empowerment.